by Elif Kalaycioglu, Political Science

A key goal for my hybrid, advanced seminar this semester is to get students to think about the multiple roles that expertise plays in diverse domains of global politics. This requires familiarity with a range of IR theories on expertise, as well as linking these theories to concrete case studies. I have found this last link to be a trickier one for students to make. They can get excited about the real-world cases, like the role of experts in devising structural adjustment programs at the IMF. They also develop in-depth comprehension of abstract theories with the aid of some lecturing, in-class discussions, and clarifications.

However, the last link of how a particular case is illustrative of certain theoretical dynamics can still be challenging to make. Not to mention, all this work is taking place under the broader context of a pandemic, when students can feel overwhelmed, unmotivated, or less engaged in an online medium.

The last link of connecting theoretical insights to real-world cases requires active engagement and critical thinking. To get the students motivated towards more active participation, I have been experimenting with role-playing exercises. These exercises have been at different scales, from short hypothetical situations to a whole class that was devoted to “acting” a chapter from a book. The chapter traced the genesis of “transnational population governance,” based on field-theory, which argues that once governance fields are established, they place actors in hierarchical positions, based on their “capital.”

On Monday, we grappled with the theory, focusing on its key concepts and propositions. At the end of our class, I assigned them roles and asked them to read the case study chapter with attentiveness to their role, thinking about what their “capital” was, their position in the field of governance, and their relation to other actors.

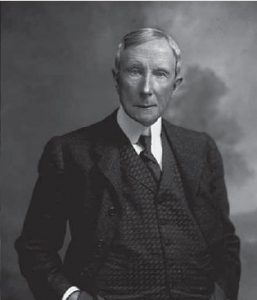

I scheduled our Wednesday class as online-only, as I believed that it would be easier for students to share the same medium, even if that medium was a Zoom session. To that Zoom class, they came prepared, ready to act their part, including a student who not only acted but also dressed the part of the key protagonist John D. Rockefeller III, complete with a suit and tie.

My preparation consisted of writing stage directions. I wrote stage directions for a play in three acts, which corresponded to three main parts of the chapter. I used the stage directions for setting the historical and political context of the case study, signaling the background information that was critical. I also wrote in cues, such as “John Rockefeller enters the stage” to invite them to perform their part. I did not interfere in their performance. If they neglected key information, I added it narratively after they were done speaking.

As the play proceeded, I realized that some students, with smaller roles participated less than they could have. In such instances, I used private messages to encourage participation. For instance, in a scene where demographers, women’s health activists, and Mr. Rockefeller were discussing population control in an even-headed manner, I encouraged the anxious Malthusian, via private messages, to enter the stage and make his alarmist intervention about population rise. This experience made me realize the importance of thinking about creative ways to involve students who are not directly participating in particular moments.

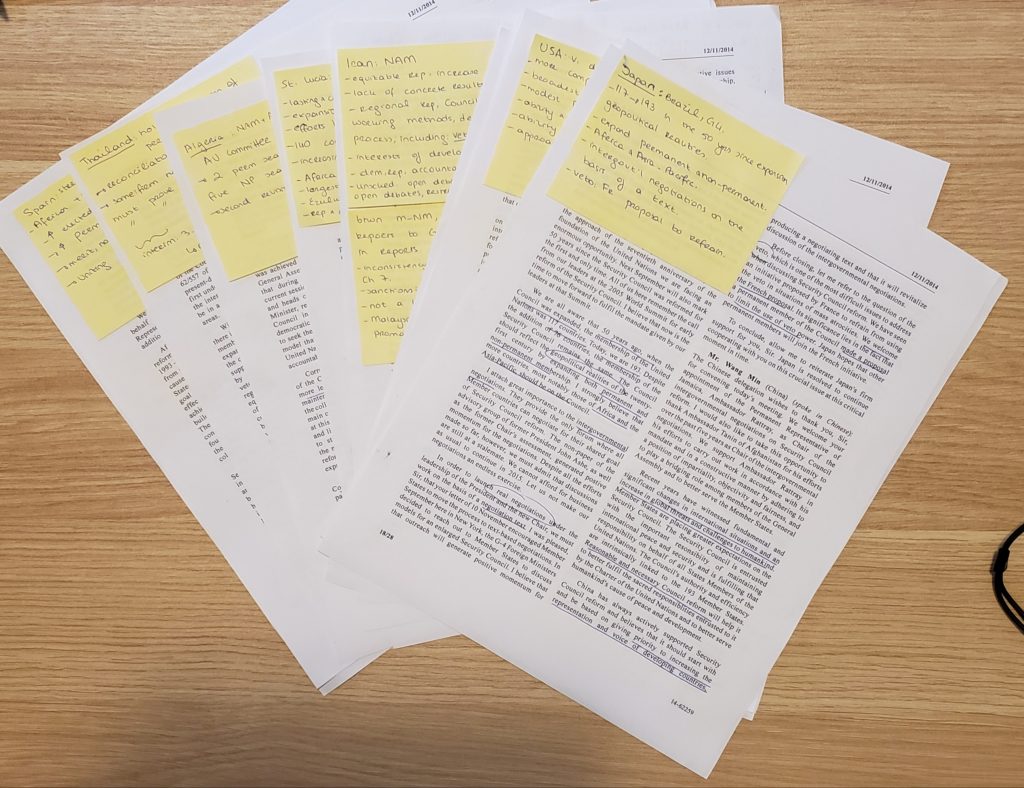

A week later, when I conducted a similar exercise in an online-only, 300-level class with 40 students, who were reenacting a UN General Assembly debate, I asked them to use the applause and thumbs up reactions whenever a speaker expressed a position similar to theirs. This produced much more active engagement with the exercise, beyond their roles.

Returning to the earlier example, after each act, we discussed what had happened. Why had their characters acted in the way that they did? What happened as a result? How did the plot move? What did that movement mean for their character, the perspective or position they represented? These discussions connected the case to the key propositions of the theory on social capital, the establishment of governance fields, and the hierarchical authority relations within those fields.

As I continue to use roleplaying in both my classes, I see more clearly how it allows students to “work through” examples and cases in a much more engaging manner. They understand the different perspectives involved, both on their own terms and in relation to one another. The issues, be it global population governance or UN Security Council reform debates, get lifted off the text and become vividly animated. When students animate the different perspectives through the characters they play, they can let disagreements emerge without worrying that they are contradicting their classmates or the professor.

I have also found that my engagement with the roleplaying, either by taking on small characters or reading stage directions, makes it easier for students to participate. It creates a setup in which we are all roleplaying, and I am not standing to the side and judging their performance. And, while roleplaying makes Zoom more interactive and energized, I suspect the distance and virtuality of Zoom also helps alleviate performance anxiety!